Fred Rose, Rotary Club

|

| Andy, our Team Leader, is going down the Class IV rapids first. Notice the rug at the front of the raft to protect it if/when hitting sharp rock walls. |

Of Men and Caribou

Caribou have long been vital to the survival of

Indigenous people in the north: the First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. There is archaeological evidence linking

people and caribou in the Yukon as early as 25,000 years ago. Although attenuated, that connection

continues to the present day.

The caribou contribute food, clothing, tools, shelter,

bedding, rugs, sails, drums, dog whips, crafts, toys (dolls), and more. It has been estimated that an Inuit family

living on the Arctic Coast needed about 30 caribou to supply all of the

clothing and bedding requirements for a year.

The Gwich’in (Athabaskan speaking First Nations and Alaska Native) say a

lack of caribou meat has been known to change people’s behavior and put them in

a bad mood ‘people are caribou and caribou are people’.

In their language, there is detailed terminology for

all stages of the lifecycle of the caribou.

They have distinct names for bulls and cows during the first, second,

third and fourth years, as well as mature and immature bulls and cows (e.g.

young bulls, breeding bulls, young cows, pregnant cows, cows with calf).

The best caribou hunting period is late summer to

fall. This is when the caribou have the

most fat, and their hides are at their best for making clothes. However, bulls are usually avoided during the

fall rut as hormones make the meat taste less pleasant. The only essential nutrient that is not found

in caribou is vitamin D.

Some Inuit believe caribou meat should never be sold,

only shared. Others argue that they need

to sell the meat to cover the increasing costs of hunting.

Today, about 50% of locals don’t get enough caribou

meat to meet their needs due to a lack of availability (as in located too far

away or in a bad location for harvesting).

The total harvest of caribou is difficult to assess but based on

available data, it may range between two-ten animals per household/annually in

communities located within the fall/winter ranges. This is well below reported

harvests in the 1950’s, which were thought to be closer to 100 caribou per

household/year.

.png) |

| Picture by Tyler Garnham (photographer and guide on this tour) I am, again, looking for wildlife with a 45x telescope |

|

| Where Porcupine Caribou Herd (PCH) was found in December 2024 From www.pcmb.ca |

|

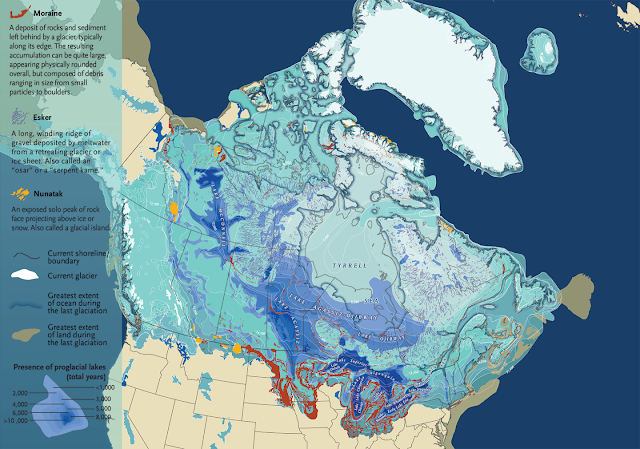

| Upper left corner at the junction of Alaska & Yukon is brownish Indicating unglaciated land |

|

| All three rafts made it past the Class IV rapids. Worth around $12,000 each (in Canadian funds), they can last 20 seasons. |

|

| Can you spot the three Dall sheep in this picture? They are so hard to see but we did see many of them during this trip. |

|

| Now we are surrounded by near vertical rock walls. |

|

| An arch in the making? |

|

| Bluebell (lungwort) |

One of the hardiest insects in the world, these moths

survive Arctic winters frozen, shortly emerging in the warmer days of

summer.

The Arctic Woolly Bear is a true survivor since it has

to withstand some of the harshest conditions on the planet (as low as -94F, -70C,

below freezing). The Arctic Woolly Bear

has to overwinter in its larval form several years in a row before becoming a

full grown moth (7 to 14 years).

While covered in ice and frost, these tiny creatures

depend on cryoprotectant (they produce glycerol, a type of antifreeze) to stay

alive. Up that far north, the summers

are so short and their food demand is so high that even a full day spent eating

is not enough to satisfy the larva’s immense appetite. Only 5% of their lives are spent eating their

favorite food, the Arctic willow, mostly in June.

When the caterpillars reach full maturity, they

initiate pupation at the beginning of summer by constructing a dual-layered

silk cocoon. This cocoon creates a hibernaculum, containing a pocket of air

between the layers. It is worth noting that the mortality rate during this

stage amounts to 13% even though these cocoons also protect them from

parasites.

In their hibernation period, caterpillars opt for

rocky areas. The presence of rocks in their surroundings provides them with

more consistent temperatures compared to the fluctuating conditions of the

surrounding soil. This choice helps minimize the potential damage resulting

from freezing and thawing cycles. Additionally, during springtime, rocks are

more efficient at absorbing heat than vegetation, which facilitates the melting

of snow and encourages the caterpillars to emerge earlier.

As adults, these moths only have two weeks to find a

mate and reproduce, before dying.

|

| Arctic Woolly Bear Carterpillar - The oldest caterpillar in the world Check out a video about this critter: https://youtu.be/eHzEOrtKA1Q |

|

| Around the corner - where we are headed |

|

| Horseshoe, left is where we came from |

|

| Orange lichen on a rock indicates some type of acid, like uric acid from birds. Great way to spot where birds hangout. |

|

| No fires are allowed in the park so someone built a fake one. |

‘That’s

where our stories are – in the caribou… that is our language; that is our

culture.’

Anastasia

Qupee

|

| The white stuff along the river's edge is not soap scum but caribou hair. Indicating they crossed the river upstream. |

|

| Close up of their hollow guard hair. The annual mean air temperature here is 37F (3C) |

|

| When there is no trees or large rocks to tie the rafts to, they use a paddle and weigh it down with rocks. |

|

| Not an Aifeus but snow piling up from a windy ledge. |

|

| We are nearly out of the canyon area, almost in the arctic coastal plains. |

So named for their birthing grounds along the

Porcupine River which runs in both Alaska and Canada, porcupine caribou are

also called Grant’s caribou.

Over the course of a grueling journey from their

winter range in the boreal forests of Alaska and NW Canada a single caribou can

travel more than 1,500 miles (2,400km), navigating mountains, river crossings

and desolate Arctic tundra to get to the calving grounds to which they’ve

returned, year after year, for centuries.

This unique environment is home to relatively few predators and is rich

in food sources for pregnant caribou and new mothers, whose calving period

coincides with the explosion of plant life that blooms in the area when the

snow subsides after the cruel Arctic winters.

The winds, coastline and ice buildup along the rivers of the coastal

plain provides crucial respite from the relentless insects that pose a serious

threat of death and disease. Caribou

also like to rest where they can see predators from a long distance.

Theirs is recognized as the longest land migration in

the world. Three times longer than the African

wildebeest migration which I was lucky enough to see in 2018.

Watching these animals assemble in the thousands is a breathtaking spectacle. What is also amazing are the sounds. Caribou produce a characteristic clicking sound as they walk due to tendons snapping past the sesamoid bones in their foot (it almost sounds like castanets), calves keep calling their mothers, and they breathe quite heavily. By listening to the clicking sounds, they can perceive the distance, direction, and speed of other individuals within their vicinity. This allows reindeer to adjust their movements, accordingly, ensuring they stay close together and do not get separated, which is crucial for their collective survival. Young caribou do not click and no one knows at what age they start to do so.

Predators

- Golden Eagles are the most important predator of calves.

- Migrator wolf packs kill between 3-5% of the herd each year.

- Grizzlies eat calves and adults.

- Wolverine kill newborn calves, cows giving birth and other weak adults.

- Mosquitoes: these micro-predators can take as much as half a cup of blood every day from an adult caribou. Mosquitoes can irritate caribou so much that they get distracted from eating. They can prevent cows from nursing their young and can drive them to the point of injuring themselves as they rush about trying to get away from them.

- Humans kill caribou each year, either intentionally by hunting them or accidentally by stressing them out. Getting chased or disturbed by snowmachines or aircrafts can cause a chemical build-up in the caribou’s muscles, which can kill the animal long after the actual event. Panicked caribou can also get injured running or get frostbite in their lungs from panting in extreme cold. Don’t chase the caribou…

|

| Caribou crossing the river in front of us. |

|

| The majority going left, but some going right (can't quite figure out why). Little ones following their mom. |

|

| Shaking the water off as they make landfall. |

|

| They are strong swimmers but we did see a couple dead ones floating downstream. |

The name caribou in English is likely derived from the

indigenous (Micmaq) word xalibu meaning ‘one who paws’ or ‘shoveler’.

At one point, Rangifer Tarandus, separated to develop

under different geography and climates. They are, therefore, subspecies of the

same animal. Reindeer (Rangifer

Tarandus) are in Asia and Europe, they do not do herd migration, they can be

wild or domesticated, and have sharp, pointy antlers. Caribou (subspecies Rangifer arcticus

arcticus, syn. R. tarandus groenlandicus) are in North America, do

herd migrations, are not at all domesticated, and have tall, curved

antlers. They have also been known as

Grant's caribou (R. a. granti; subsequently R. t. granti).

Reindeer adaptation to the cold was followed by human

domestication, meaning they no longer felt the urge to migrate. Few wild reindeer still exist in Greenland,

Norway, and Russia.

Both reindeer and caribou can be found in Alaska but

have different lifestyles. Reindeer were

brought in from Europe in 1892 (by Dr Sheldon Jackson) and have been

domesticated by people. In contrast,

their wild counterparts are caribou and have never been domesticated.

|

| See how steep the hill they are coming down from is? |

|

| Wet and a bit distressed by our presence. |

|

| Moving away from us. |

.png) |

| Another young one going into the water |

- They are called barren-ground caribou and they migrate (woodland caribou do not).

- Males and females have antlers.

- The Caribou became extinct in the contiguous USA in 2019.

- Bulls weigh 200-300 pounds, cows 150 pounds.

- Calves stand within 30 minutes of birth and move with the herd within a day.

- They are built for the coldest of climates. They have hair on every part of their body, including their nose and hooves.

- They eat lichens (which I will not see until I get to the Nahanni River – picture in next post) as a primary winter food source, which enables them to survive on harsh northern rangeland. In the summer they eat sedges, grasses, and shrubs. Willow, alder, Labrador tea, and mushrooms are also documented sources of food. Caribou are drawn to some muds as salt licks.

- Their feet make a unique clicking sound, so a large herd makes a lot of noise when running. The clicking sound is amplified due to the structure of the leg bones, which acts as a natural resonating chamber. This noise helps them stay together when visibility in a blizzard or thick fog is poor.

- They give birth in late May, early June.

- They are very skittish around humans.

- They can reach 50m/h (80km/h) when sprinting.

- They are excellent swimmers, going as fast as 6.25m/h (10km/h).

- The highest number of points ever reported on a male was 44!

- Every fall, their hooves grow sharp edges to let them break through ice in search of food.

- Their tapetum lucidum, the layer of cells behind the retina in the eyes that helps animals see in dim light, changes color throughout the year. It is golden in the summer and turns blue in the winter. This color change is induced by seasonal variation in daylight.

Caribou herds grow and shrink naturally over 30 to 65

years. Inuit elders have described how caribou in decline move to find better

food. They eventually repopulate areas once the vegetation recovers, which

takes about 20 years. Using Indigenous knowledge to identify, map, and protect

these areas is important in helping caribou to recover.

%20-%20cpaws-sask.org.png) |

| From cpaws-sask.org |

%20-%20canada.ca.png) |

| From www.canada.ca Cumulative effects of various influences to caribou populations |

|

| Caribou Herd Ranges In blue, the ones we saw |

%20-%20pcmb.ca.png) |

| www.pcmb.ca Various statistics about caribou population/life |

.png) |

| Beautiful female red fox She had a little one with her but it was hiding away |

.png) |

| Beautiful fur coat Windy day |

This hill is situated within the portion of the Yukon

Coastal Plain that was overridden by ice during the Buckland Glaciation of the

late Quaternary Period. Consequently,

the plain immediately adjacent to Engigstciak represents a moraine, a landform

made from debris left behind by a glacier.

Projecting about 115 feet (35m) above the surrounding

plain, it offers stunning and unobstructed views of the treeless tundra,

including views upstream and downstream along the Firth River, across the

coastal plain towards Herschel Island to the NNE, and towards the adjacent

foothill and mountain areas to the NW, SW, and SE.

This hill is an obvious vantage point to scan for

caribou or other large animals, particularly since the Firth River canyon –

located just upstream is a natural obstruction to the East-West migration

routes, and thus tends to direct migrating animals northward towards the

Engigstciak area and beyond.

Archeological investigations on the plain west of

Engigstciak have revealed that use of the site began at least 11,000 years ago

and continued into the Thule Inuit period (200 BCE to 1600 CE). Found

nearby were stone scrapers, burins, projectile points, antler flakers, bone

needles, and pottery, making this area one of the most important archaeological

sites in the Canadian Arctic.

|

| Panoramic view of the mountains we are leaving behind. We are on top of Engigstciak (meaning The New Mountain) Great vantage point to scan for caribou and other mammals. |

From www.nahanni.com

Nunaluk Spit is a place unlike any other. Here, the

Firth River meets the least-explored ocean on our planet: the Arctic Ocean, a

place where the intensity and vibrancy of the North never disappoints.

Made of sediment and stone pulled from the mountains,

shaped by water and continuously combed by ocean currents, this landmass

bridges the terrestrial and the marine. This is a place where muskox walk the

shores of the Beaufort Sea while beluga feed on Arctic char; where terns, snow

buntings, gulls and plover circle overhead; where tracks of wolf, muskox,

caribou and grizzly give testament of an active wildlife corridor. When we visit,

we have witnessed seals and beluga past.

We often find their bones amongst the driftwood—some storm-tossed and

some recently thawed from the permafrost in a melting Arctic.

On the way to Nunaluk spit, we also saw tundra swans,

red throated loons, and eider ducks. Although

we didn’t see any muskox, we certainly found a lot of their amazingly soft under-fur

(qiviut) garlanding the many bushes they had brushed up against during their

molt.

The East end of Nunaluk Spit, is rapidly eroding. At

its center lies a permafrost core that disintegrates further with each storm.

This past summer, a trapper’s cabin that was a well-preserved landmark for the

last century gave in to the sea; now only a few logs, washed above the

tideline, remain to tell of the region’s recent occupants. But as the ice melts

and some history is lost, another much-older connection to the past is

revealed. Over the years our guests have found tools such as snow knives, sled

runners and a myriad of ancient bones.

Currents carry driftwood westward, from the mouth of

the Mackenzie River, dispersing logs along thousands of miles of coastline. The

logs provide essential habitat for a variety of small mammals and nesting

birds. In the past, humans depended on driftwood for warmth and shelter while

on the coast. The many driftwood shelters, sod roofed huts and grave sites are

evidence of this. Each one of our tents

was protected by such driftwood logs.

The combined currents of the Firth River and the ocean

creates a rich marine environment where seals and beluga feed. When these

species die, they, in turn, provide large mammals like wolves and grizzly bears

access to the riches of the sea when they wash up on the shore.

|

| Moving the rafts to the spit - last of the trip. |

|

| Icebergs floating by and long line of ice in the background. Sea of Beaufort. 69.555 latitude |

|

| All this stuff is cleaned, sorted, and packed ready to be put into planes headed back to Inuvik. |

|

| It's amazing how well organized this whole trip was. Repair kits, first aid kits, extras for anything (boots, sleeping bags, oars, etc.) |

|

| Found the skull of a precursor to horses (much longer head). The Yukon horses disappeared 12,000 years ago. |

|

| Bird flying by interestingly shaped iceberg that turned upside down as soon as I took that picture. |

|

| My tent - last night of the trip. Protected by driftwood found on the beach & built over several seasons. |

|

| Washing the empty rafts. |

|

| Last rinse. |

|

| Stacking the rafts on top of each other to get the air out of them and dry them. They will be rolled up tight to fit in the planes. |

|

| My first and only 'fogbow'. White rainbow-like but lower to the ground. |

|

| Fogbow. The lack of colors is caused by tiny fog droplets which are much smaller than raindrops and therefore, do not 'filter' colors. Most drift wood comes from the Mackenzie River in the NWT |

|

| Purple Bittercress (cardamine) |

|

| Catchfly (silene) - small pod-like flowers on the right I had those for dinner at Hiša Franko (Michelin ***) in Slovenia |

|

| Panoramic view of lagoon - background of the mountains we left behind |

|

| King Eider eggs (the feathers lining the nest are super soft and warm). Found in warm clothing or comforters. |

|

| Last fire (allowed only on the spit - nowhere else in the park) To help warm up after a dip in the Sea of Beaufort. |

|

| Returning with Aklak Air Many pilots only work here in the summer, going south in the winter One of our pilots, spends his time sailing the Sea of Cortez in the winter. |

|

| The opening of the Firth River Lagoon to the Sea of Beaufort I stopped counting at 300, the amount of beluga whales I saw from the air on the way back |

|

| All of these braids going into a brackish lagoon full of sandbars and silt Can you imagine trying to pick the correct channel? |

|

| These are called tundra or ice wedge polygons. Interesting formation created by ice wedges over time. Only happens where there is permafrost |

|

| A return to tundra lakes and ponds as well as a large river on our way back to Inuvik. What an absolutely amazing trip this was. |

During much of the ice age, small brightly colored

tundra flowers blew in the cold wind in a dry grassland. They were later replaced by the stunted spruce

forests and boggy tundra ponds that are so prominent today. It’s hard to imagine that in those days, ice

age hunters were more likely to see a camel, a beaver the size of a bear, or a horse

along the shores of a giant glacial lake than a muskox trudging through the bushes.

The river is a true classic of wilderness, archeology

and whitewater as it flows through a pristine wild arctic landscape and through

a canyon filled with Class II to IV whitewater in an area that hasn’t seen

human occupation for at least 12,000 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We are always happy to hear from you but at times it may take a while to get a reply - all depends if we have access to the internet.